ANDY ADKINS

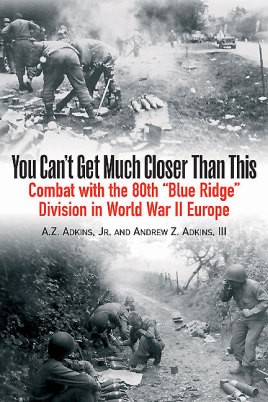

You Can't Get Much Closer Than This

Combat with the 80th "Blue Ridge" Division in WWII Europe

Published by: Casemate Publishers

Release date: June 2005

Format: Paperback, eBook

ISBN13: 9781612003108

Pages: 288

Buy the Book: Casemate, Barnes & Noble, Amazon

![]() Video Presentation: "You Can't Get Much Closer Than This."

Video Presentation: "You Can't Get Much Closer Than This."

"Livestreams: Learning from the Home Front." Presented by the Virginia War Memorial. January 18, 2022.

![]() Audio Podcast: "Author Andy Adkins III discusses his book, "You Can't Get Much Closer Than This."

Audio Podcast: "Author Andy Adkins III discusses his book, "You Can't Get Much Closer Than This."

Presented by William Ramsey Investigates. August 21, 2021.

![]() Audio Podcast: "Andy Adkins discusses his book, "You Can't Get Much Closer Than This."

Audio Podcast: "Andy Adkins discusses his book, "You Can't Get Much Closer Than This."

Interview by Charlie Bee, KBUL Radio, "The Bulletin." November 18, 2005.

OVERVIEW

After graduating from The Citadel in May 1943, Andrew Adkins, Jr. immediately attended the U.S. Army Officer Candidate School, where he was commissioned and sent on to the 80th Infantry Division, then undergoing its final training cycle in the California-Arizona desert. Upon reaching the division, 2d Lieutenant Adkins was assigned as an 81mm mortar section leader in Company H, 2d Battalion, 317th Infantry Regiment. When the 80th Infantry Division completed its training in December 1943, it was shipped in stages to the United Kingdom and then on to Normandy, where it landed on August 3, 1944. There, Lieutenant Adkins and his fellow soldiers took part in light hedgerow fighting that served to shake the division down and familiarize the troops and their officers with combat.

The first real test came on August 20, 1944, when the 2d Battalion, 317th Infantry, attacked high ground near Argentan during the Allied drive to seal huge German forces in the Falaise Pocket. While scouting for mortar positions in the woods, Andy Adkins ran into a group of Germans and shot one of them dead with his carbine. This baptism in blood taught him the answer to a question every novice combatant wants to hear: He was cool under fire, capable of killing when facing the enemy. He later wrote, "It was a sickening sight, but having been caught up in the heat of battle, I didn't have a reaction other than feeling I had saved my own life."

Thereafter, the 2d Battalion, 317th Infantry, took part in a succession of bloody battles across France. Ineptly led through the tenures of several battalion commanders, the unit suffered grievous losses even as it took hills and towns away from brave and well-led German veterans. In the course of fighting graphically portrayed in this soldier's memoir, Andy Adkins acted with remarkable skill and courage, placing himself at the forefront of the action whenever he could. His extremely aggressive delivery of critical supplies to a cut-off unit in an embattled French town earned him a Bronze Star Medal, the first such award in his battalion. You Can't Get Much Closer Than This is at heart a young soldier's story of war. In vibrant, piercing terms, a junior officer's coming of age in battle is the compelling focus of page after page of action sequences.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Chapter 1: The Making of a Soldier

- Chapter 2: First Taste Of Battle

- Chapter 3: Crossing The Moselle

- Chapter 4: Hill 382 (St. Genevieve)

- Chapter 5: Villers-Les-Moivron [Read Excerpt]

- Chapter 6: Sivry, France

- Chapter 7: Medical Evacuation And Recovery

- Chapter 8: Back To The Front

- Chapter 9: The Battle Of The Bulge [Read Excerpt]

- Chapter 10: The Relentless, Bitter Cold Winter

- Chapter 11: The Siegfried Line

- Chapter 12: R&R In Paris

- Chapter 13: Marching Onward

- Chapter 14: Crossing The Rhine

- Chapter 15: Moving Fast

- Chapter 16: Buchenwald [Read Excerpt]

- Chapter 17: Nuremberg

- Chapter 18: The End Of The War

- APPENDIX 1: The 80th Infantry Division

- APPENDIX 2: Infantry Organizations

REVIEWS

"Andy Adkins III put together an incredible work, using the diary of his father, Lt. Andrew Adkins,

who led a mortar company from France into Luxembourg and Germany. Adkins' journal tells the horror of war

but also the close bonds that soldiers form under such terrible conditions. The book is well-written,

but made even more compelling by the character of Lt. Adkins who displays bravery, integrity, and compassion.

A marvelous book."

-Amazon customer

"It is a fascinating account to read of a junior officer learning his trade in difficult circumstances,

but where he earned the respect of his men. A personal record like this is a valuable resource to anyone

interested in the period and made available to us thanks to his son, Andrew Adkins III.."

-Military Modelling

"The 80th Division came ashore at Utah Beach shortly after D-Day and was one of the key units in Patton's 3rd Army.

They were in the thick of the fighting during the Normandy breakout through the Battle of the Bulge and the final

days of the war. This book is an edited version of the combat diary of a Lieutenant in one of the 80th Division's

infantry regimenta. The veteran's son edited the diaries and produced the book. The son is also the division's historian,

having assembled an exhaustive reference web site of everything 80th Division: division, battalion and regiment monthly

after action reports and unit histories, company morning reports, key after action interviews, etc. It's an excellent

combat history and personal story. The author writes very well and is not afraid to give his opinions.

You learn about his buddies, his views of the unit's commanding officers (not always flattering), and the battles

they were in. Excellent perspective on the war."

-L.S. Reed

EXCERPTS This is my father's letter to his parents the day after the Germans surrendered.

Austria

8 May 1945

Dearest Mom & Dad,

Shortly after I wrote to you day before yesterday, I received the cease fire order.

At that particular time I had my shoes & shirt off & was playing with a little dog on the grass of some Austrian's yard. My men were all in houses taking it easy. My battalion had momentarily stopped in a little mountain village.

I told the first sergeant to assemble the company. As my men came marching up, a big lump formed in my throat because many familiar faces were missing from the files of men who were to hear me read to them General Eisenhower's order that hostilities had ceased.

I told my men to sit down & take it easy & that I had something to tell them. Then I read to them General Eisenhower's order telling of the unconditional surrender. When I finished no one said a word. Finally, one man said, "Lieutenant, read that again please."

The day that we had died & bled for so long had finally arrived. No one knows what the word peace means except those who have been at war. As yet I feel no great emotional change. But gradually, I am beginning to realize that there will be no more suffering & no more dying & the sensation is truly wonderful.

Tonight, I am in another mountain village high in the Bavarian Alps. I have a radio & can listen to the celebrations that the people in England & America are having. Here, we are having a different type of celebration. Ours is a quiet celebration. We still have to maintain order, but we are so happy & it's hard for us to realize this mess is over.

I love you both dearly.

Devotedly,

Andy

Chapter 5: Villers-les-Moivron

All infantrymen know they will get hit. It's just a matter of time. They don't talk about it much, but they all know that sooner or later their turn will come. They just pray to God that when their time does come they won't get hit in the guts or in the face. Anywhere but in the guts or in the face.

Several artillery shells landed on top of us as we hugged close to the ground. Sergeant Martin Roach got hit in the back and legs, and was screaming in pain. Sergeant Volk tried to get up, but he couldn't; both his legs were broken. I was knocked out for a little while. When I regained my senses, I heard Private Freeman yell. He was one of Bill Butz's boys. He had a hole all the way through his side, and he was hurting bad. I cut his shirt off, saw that I couldn't help him, and had someone carry him to the aid station. Sergeant Ralph Freeman, my platoon sergeant, was dazed from a concussion. I slapped him a few times and he came to. I lost nine men in the one little barrage, so I told Kad to get the hell out of there, into the draw behind us.

Company F couldn't move, so the major decided to send Company E through with tanks from the 6th Armored Division. Five Shermans came up the road with riflemen alongside. Lieutenant Henry Walker's rifle platoon was leading, and as usual he was up front with the first tank. I grinned and yelled, "What the hell's the matter? You getting scared and have to have tanks with you?" He grinned and yelled, "Hell no. But I do know that my life's not worth two cents!" That was the last time I saw Hank alive. He was killed a few minutes later.

Chapter 9: The Battle of the Bulge

We moved out when darkness set in. The moon shone brightly and it was very cold. We had frozen C-rations and frozen blankets waiting for us. Kad and I got the mortars placed and then tried to figure out some way of heating our frozen rations. There was a burning farm house nearby, so we thawed our rations there, then we decided to see if we could get some sleep.

We found 1st Sergeant Bloodworth and Lt Bill Mounts huddled in a chicken coop. It was the only thing left standing on the farm. They had a little fire going, and chickens were roosting. Between the smell, the smoke, and the cramped conditions, it was almost impossible to breathe, so Kad and I moved outside.

It was Christmas Day. At first light, we got orders to saddle up and move back. We were to dig in on the high ground about a mile north of Niederfeulen. We were in regimental reserve while 1st and 3d battalions attacked Kehmen. What a way to start Christmas Day. The head of our column moved slowly and, as a result, the men began to bunch up. The Krauts noticed this opportunity and opened up on us with artillery as we moved up the side of a hill. They were firing screaming meemies--large-caliber rounds fired in clusters. We heard the rockets coming, but there was little we could do other than spread out and run like hell. There was no cover around.

The German Nebelwerfer was equipped with five rockets. Due to its design, the rocket made a screaming sound as it flew through the air. They used high explosives but were not very accurate. They would, however, scare the crap out of you. Hence the name "screaming meemies."

Several men were hit. Some of the men hit the ground and wanted to stay there. That would have been suicide, but it was tough to get them up and keep them moving. When we got over the top of the hill and out of sight, the Krauts stopped shooting at us.

We were to set up the 81s behind Company G. A small patch of woods was near our proposed position. We had to search and clear that area first. We found two dead frozen Krauts who had been killed during the first part of the breakthrough. About two hundred yards from the guns was a huge house.

It was Christmas Day. Kad and I were determined to get our men warm. We went to investigate the house and found that an antiaircraft outfit had been there before the breakthrough and, from the equipment and supplies left behind, it was easy to see that they had moved out in a hurry.

We left a skeleton crew with the mortars and moved the rest of the men into the house. The company and battalion CPs were in Niederfeulen, so I went to see Bill Mounts to find out what was cooking. Junior, my runner, went with me. The Krauts were shelling the town and it was difficult to get around, but we finally found Bill. He was sitting in the cellar of a house, eating apples.

When you're within range of German artillery, you want to be in the cellar. In many cases, the first and second floors had been blown away, but even if they weren't, they were inviting targets for German artillery. Anyone other than a front-line battle infantryman walking into one of those cellars would immediately consider it uninhabitable. It smelled bad--the air was a mixture of sweat, brick dust, soot, cigarette smoke, and oftentimes urine. It would not be breathable by a normal human being. But, every infantryman who was lucky enough to find one of those cellars thought it the most desirable place on earth. They were secure from all but a direct artillery hit. Most important, they were dry and out of the direct weather. The exhausted trooper could push some straw into a corner, lie down, and plunge into a deep sleep, completely relaxed.

Chapter 16: Buchenwald

The next morning, April 13, we took another little town without any trouble. It was near Weimar, the birthplace of the German Republic in 1919. The division had been given the mission of taking it and the Buchenwald concentration camp, located about three miles to the northwest. My battalion was to take and hold a little town on the flank of Weimar while the 319th Regiment took Weimar itself. We had heard rumors about the atrocities, but we had no idea of what we were about to encounter.

On the outskirts of town was a little hill. Bill Butz and I went with Major Williams to the top of the hill for a look-see. We had been there only a little while when we saw six men, formed as skirmishers, coming toward us with their rifles at their hips. Naturally we spread out and took cover. This would have been a hell of a time for the Krauts to attack us as all of our men were just moving into town.

We looked through our glasses. The men heading toward us were not wearing helmets. When they came closer we saw their striped pants and shirts and knew they were escapees from the concentration camp. When they got to us we found out they were Russians. They told us what had happened.

Fifteen thousand of them had overpowered their SS guards at Buchenwald. They had taken their weapons and went out to kill Krauts, particularly SS. Major Williams was a little skeptical. About that time one of Company G's scouts brought up an SS soldier he had caught in the woods. The major pointed to the Kraut and told the Russians "Him SS." One of the Russians said, "Give him to me." Then he kicked the SS man and told him to start running. He ran only twenty yards before he had more holes in him than a sieve.

We later became more acquainted with the Russian escapees and learned a lot about daily life in the concentration camp. Two of them were infantry lieutenants who had been captured at Stalingrad. They wanted to stay with us and fight with the Americans until we met up with the Russians. When we got to Weimar, the major put them into GI uniforms. They were happy to take care of any SS troops for us.

Lieutenant George McDonell, Company E's CO, and one of my machine gun platoons were guarding and maintaining order at the Buchenwald concentration camp. Buchenwald was horrible beyond description. There were thousands of prisoners there composed of every nationality, creed, and color in the world. Twenty different languages were spoken there.

I walked into a prisoner barracks with McDonell. A hundred men could have arranged themselves comfortably in there, but the Krauts had crowded in a thousand men. There were wooden bunks from the floor to the ceiling, just like shelves. Once a man got on his "shelf" he didn't even have enough room to turn over.

Some of the prisoners had a thin, stinking blanket. Others had none. Some were too weak to get up, and they looked at us with dull eyes, not realizing who we were or what was going on. To say that they were nothing but skin and bones is not enough. They had ugly looking sores, swollen ankles, and their minds were deranged.

Everything stank. General McBride came out and inspected Buchenwald. He then ordered all the windows to be broken out and said he would send several truckloads of blankets down. Of course, higher echelons were sending medical staffs and food. There were more than twenty thousand prisoners still in Buchenwald by the time the 80th Division arrived. This was the first major German concentration camp to fall into Allied hands while it still had a full population of prisoners.

Outside were thousands upon thousands of naked bundles of skin and bones, their torsos and faces twisted in all sorts of grotesque designs. Bodies were stacked on top of bodies, neatly arranged, and stacked like cords of wood. The stack was about five or six feet high and extended for about fifty feet. All were dead, all were naked, all were face up. It was a sickening sight, because beyond this stack of bodies were more stacks of bodies.

Then we discovered the crematorium. Set in the brick walls were small openings with iron doors about two feet wide and two feet high. There were several sets of these doors, most were closed, but we found one open. Inside, were heavy metal trays with partially burned bodies. It looked like each tray could hold three bodies at one time.

Toward the end of the war, it was estimated that about five thousand prisoners died each month at Buchenwald. We found one huge hole where thousands of naked bodies had been dumped. The Krauts had tried to burn the bodies to hide the evidence, but we had gotten there too soon. The smell of death stayed in my nostrils for days.