ANDY ADKINS

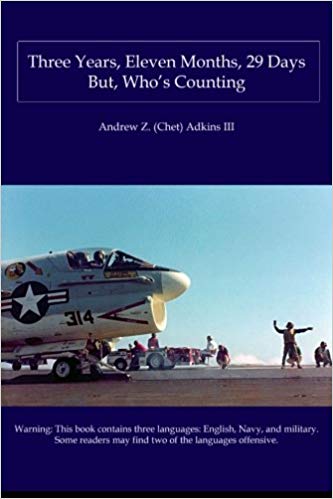

Three Years, Eleven Months, 29 Days

But Who's Counting

Published by: AZAdkinsIII

Release date: August 2014

Format: Paperback, Kindle

ISBN13: 9780615931012

Pages: 258

Buy the Book: Amazon

OVERVIEW

At eighteen years old and without a clue as to what he wanted to do with his life, Andy ("Chet") Adkins joined the Navy that not only taught him discipline and leadership, but also helped him mature into a confident man.

Three Years, Eleven Months, 29 Days - But Who's Counting is a book about growing up in the Navy, including all the good, bad, and indifferent. The Navy is full of traditions and Adkins captures the essence of these timeless military honors. His experiences in both land and sea assignments offer a unique insight into the daily events of a modern day Navy man.

After flunking out of college, Adkins takes you from induction, through boot camp and "A" School, and through his three tours: NAS Agana Guam, USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63), and the Bremerton Shipyards, all the time with detailed daily life in the Navy, both on duty as well as off duty.

Whether you are currently serving in the Navy or any branch of service, you'll relive a lot of your own experiences, good or bad, through the eyes of a Navy man. If you are contemplating joining the Navy, this will be an eye opener to the wondrous adventures that lie ahead.

May God Bless all our military: those who have served; those who are serving; those who will serve.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Chapter 1 THE BIG DECISION

- Chapter 2 Checking In - Welcome To Hell [Read Excerpt]

- Chapter 3 Boot Camp - Company 163

- Chapter 4 ABH "A" School

- Chapter 5 NAS AGANA GUAM - Welcome To Paradise

- Chapter 6 On Duty

- Chapter 7 Off Duty

- Chapter 8 New Orders

- Chapter 9 USS KITTY HAWK - I'm Too Early

- Chapter 10 Welcome Aboard

- Chapter 11 A Tour Of The Ship

- Chapter 12 A Tour Of The Flight Deck

- Chapter 13 Flight Deck Operations [Read Excerpt]

- Chapter 14 Launch And Recovery Operations

- Chapter 15 On Board Routines

- Chapter 16 WESTPAC '75

- Chapter 17 Kitty Hawk Air Wing, CVW-11

- Chapter 18 Hawaii, One Word: Beautiful!

- Chapter 19 Philippines, One Word: Hot! [Read Excerpt]

- Chapter 20 Hong Kong, One Word: Tattoo!

- Chapter 21 Japan, One Word: Culture!

- Chapter 22 Heading Home, One Word: Hallelujah!

- Chapter 23 San Diego

- Chapter 24 BREMERTON - Shipyards

- Chapter 25 Life Outside the Shipyards

- Chapter 26 Winding Down in the Shipyards

- Chapter 27 Shakedown and Adios [Read Excerpt]

- Chapter 28 Decommission

- GLOSSARY

- FALCON CODES

REVIEWS

"Picked up the electronic version of this and plowed straight through. While I served in the West coast Navy well after his departure and have been out for a number of years, it was comforting and hilarious to see the similarity in experiences, attitudes, and culture that have persisted across the years welding us together. It made me hopeful that the traditions, even the painful ones, carry on. (I found myself translating Navy shorthand on the fly in my head, reminding me of that past life.) This is a wonderful book for people that have or have had Navy in their family or if they have kids looking to learn more prior to enlisting. (My oldest boy is reading it now and it has been fun talking him through my experiences, and the changes in tools and technology as he asks questions.)

"There are a lot of great day to day 'blue collar' military stories out there and this book serves as an

excellent reminder of the importance of getting those memories in print. BZ!"

-Amazon customer

"Good book shipmate. I did WESTPAC 73-74 and WESTPAC 75 on the Kitty Hawk (plus both RIMPACs), I was in VS-37 (Aircrew). I worked on the roof also, but only to load sonobuoys (which was only every few days), pre-flight, and (back seat) fly on/off the boat - 70 CATS/TRAPS. Since I did two WESTPACs on Kitty Hawk, they run together in my head 40+ years later, so your book was great helping separate the two. Chapter 19 on the PI was very tactfully written. I would like to read the real version, LOL."

"Oh BTW, smokes were only $1.10 per carton at sea, and you could get San Miguel for 1.5 pisos down the side

street of Gordon Avenue."

-Amazon customer

EXCERPTS

"Warning: This book contains three languages: English, Navy, and military.

Some readers may find two of the languages offensive."

-Author

The first couple of days we were lined up for all sorts of fun activities, starting with haircuts. By lined up, I mean we were nice and tight, or as you get more used to it, the Navy term is "Nut-to-Butt." It was funny because for those of us who grew up in the seventies, long hair was in. Most new recruits had long hair.

We were all lined up standing at attention outside the barber shop. There were about five or six barber chairs in the place. There was also about two feet of hair on the floor, almost like walking through a field of wheat. I got into the chair and while my hair was not that long, I asked the guy to "take a little off the top." Well, after thirty seconds (the barbers had a contest to see who could shave a new recruit's hair off in the shortest amount of time, sort of like shaving wool off a sheep), he was done with me and said, "How's that smartass? Now, get the fuck out of my chair." Welcome to the United States Navy.

Once done with our new crew cuts, we gathered outside in a straight line, again standing at attention. Funny thing though; I did not recognize anyone since we had all had our locks trimmed. "Is that you, Smith?" I asked someone that looked a little familiar. I'm sure I looked as funny to everyone else as they did to me.

Besides being woken up at 0400 with some asshole kicking a garbage can down the middle of the barracks and screaming at the top of his lungs some vulgar obscenities, we got into a somewhat regular routine those first few days: early morning calisthenics, three meals a day, and cleaning our barracks. I thought to myself, this isn't so bad. Was I in for a surprise.

Ch 13: USS KITTY HAWK - Flight Deck Operations

They say working on the flight deck of an aircraft carrier is one of the most dangerous jobs in the world and one of the most unforgiving places to work--there is little to no margin for error. It's loud, it's busy, it's smelly, and you have to keep your head on a swivel, constantly aware of what is going on around you. In one careless second, a fighter jet engine could suck somebody in or blow somebody overboard.

Being behind a jet exhaust is no fun, either. It stinks and sometimes it is so hot it can burn your nose hairs when you breathe in. There are usually between 175 and 200 personnel on the flight deck at any one time during flight ops. The average age of airmen on the flight deck is between nineteen and twenty years old. That is a lot of responsibility to throw at these youngsters, but most of them are one dedicated bunch.

Having worked on the flight deck, I can certainly attest to how dangerous an environment it is. But in the same sense, flight deck operations can be one of the most challenging, rewarding, and orchestrated performances you will ever witness. It takes teamwork from a group of men (and now women) who do not know each other, but they know and respect the important roles each must play during this command performance.

Flight deck operations involve many different people with many different jobs. The Navy figured out a long time ago that different colored jerseys with stenciled IDs would help to identify who does what on the flight deck. Because of these different colored jerseys, flight deck personnel are now sometimes referred to as "Skittles." Skittles is the name of a candy with many different colors; they hadn't been invented when I was in the Navy.

Ch 19: WESTPAC '75 - Philippines, One Word: Hot!

Kitty Hawk headed out to sea again for a couple of weeks of exercises. This time out would be a deadly trip. As mentioned earlier, the first aircraft off the deck for flight ops was the plane guard helicopter from the HS-8 squadron. We had a crash tractor manned on the flight deck, as we always did, but did not have a crash truck manned which was normal operating procedures. Almost all the crash crew were either in the crash compartment or just outside shooting the breeze waiting for flight ops to start.

All of a sudden, the Air Boss came over the 5MC, "Crash to the flight deck! Crash to the flight deck!" We all hauled ass out onto the deck and all we could see was a helo trying to take off. It took a couple of seconds to realize what happened. The starboard main gear had collapsed and one of the helo ground crew was dangling from the wheel well. The main wheel tie-down chains were removed, but the helo was still tied down to the deck by the tail wheel tie-down chain. The pilot was hovering over the deck at about six inches. The plane captain directing the helo was trying to help the pilot keep steady, but it was tough since the helo was still tied down with one chain.

My pal Buddy Laney was riding on the back of the crash tractor and saw it all. He told me later that it was one of the most harrowing experiences in his life, being so close to a killer helo and not being able to do anything about it. He said his training kicked in and they were preparing for the worst--a crash on the flight deck. But, like the rest of us, there was little to do with the helo still tied down still trying to take off.

Several of us dunked down with a rescue stretcher and got close to the helo. About that time, the killer helo dropped the ground crew member and we grabbed his legs and pulled him out of range of those dangerous rotors. The flight deck medic was trying to put a compress on his head, but I knew this guy was long gone. His head was squished sideways about half its normal size--blood was everywhere as well as some brain matter. I had been through enough training to do what I did, as did everyone else. We put him into the stretcher and carried him over to the #2 elevator where he was lowered down and the guys rushed him to Sickbay. My pants and shirt were covered with blood and brains.

Meanwhile the helo was still hovering just a few inches off the ground. Our Crash LPO Jeff Atteberry was on his stomach crawling toward the helo. The only way this thing could end safely was to undo the last tie-down and Jeff was going to do just that. He reached the tie-down and when the plane captain saw what he was doing, helped the pilot keep steady while Jeff undid the tie-down. The pilot flew the helo off and everyone on the flight deck breathed a sigh of relief. That was a harrowing experience.

We weren't done yet--the second part of our name was "Salvage," so we had to figure out how to get the helo and its crew safely back on board. Fortunately, we had trained for such things and had a plan. Part of our crash arsenal included a crash dolly which is a heavy metal dolly about three feet wide and four feet long with four heavy rubber wheels. We had several mattresses brought up from below decks and tied these to the crash dolly. We then anchored the crash dolly to the flight deck in the recovery area using a half dozen tie down chains.

In order to get the helo back onto the flight deck, a helo plane captain served as the director which was standard operating procedure. We parked a tow tractor in front of him so that if something bad happened, he could at least dive and duck down behind the tractor, hopefully avoiding any flying helo parts. We moved all nearby aircraft to the aft part of the flight deck—no need destroying or damaging aircraft if it could be helped.

We also had the crash truck parked on the point on the starboard side with a full crew all suited up. The rescue guy fully suited up and standing on the back of the crash truck was Steve Deaver, a big strong Texan. He had joined us in the Philippines. The flight deck was cleared of all unnecessary personnel. All of the V-1 Division was up there though. We were in the catwalks standing by with fire hoses. I got out of the catwalk and went up to the crash truck and talked with Deaver. I told him to remember his training, do not do anything stupid, and watch his ass. I don't know what drove me to give him that pep talk, but maybe I was trying to tell myself that everything would be fine.

As the helo approached, the plane captain directed him slowly over the flight deck. The first thing the pilot did was hover over the flight deck and let the helo crew out. They had about a five foot jump down to the deck. The pilot knew what needed to be done, but it took three times for him to ease down before he was able to place the helo's crippled starboard wheel safely onto the crash dolly. We had placed enough mattress pads on it so that when he landed, the helo was almost level. Once he put the full weight of the helo down, he still kept the rotors going until the blue shirts and helo crew could tie him down to the flight deck. When that was done, he cut power to the engines. He was safe, we were safe, and there is a God.

The next step was to get the helo out of the recover area. We had an answer for that too, a little friend we called "Tilly," our crash crane. Gary Borne cranked her up and drove her over to the helo, but since I had not been checked out on how to hook up the crash slings for the SH-3 helo and he had, I climbed up into the cab to relieve him. He was pissed, because driving Tilly was easy compared to hooking up the helo. But, that's the way things go. After Gary hooked up the crash sling, I was able to lift the helo up enough for the crew to strap on a temporary wheel and then a tractor, so it was towed out of the recovery area. Once the helo was down on the flight deck safely, it took us about an hour to get it out of the way to resume flight ops.

Ch 27: USS KITTY HAWK - Shakedown and Adios

We were running flight ops as we always did and I was in the crotch directing aircraft out of the recovery area. During this particular flight op, we were launching at the same time as recovering. We had recovered the first batch of F-14s and A-6s and were bringing aboard the A-7s. At the same time, we were launching F-14s on cat #2, right next to me. It was really loud when you are that close to an F-14 in afterburner, even though I was in no danger of getting blown over.

After the third A-7 Corsair landed and I taxied him out of the recovery area, I was watching the next one approach. He was flying a little awkward so I figured he was a new pilot still working on his quals and not used to landing on a flight deck. Meanwhile, an F-14 was preparing for launch right next to me and my attention was bouncing back between the F-14 in full afterburner preparing to launch and the A-7 landing. I was stooping down ready to spring into action when the A-7 landed. As it hit the deck, it grabbed a wire with its hook and the pilot applied full power as they always did. The only problem was that this A-7 pilot not only applied full power, but also pulled back on his elevator at the same time. He had the cable in his tail hook, yet he was also about ten feet off the ground fixing to make a big splat.

Let me pause here at this particular moment in time and relay to you what was going on. For one, the A-7 Corsair was in the air about ten feet above the deck with an arresting cable in his tail hook, soon to splatter on the flight deck. I was less than fifty feet away. To my left, about twenty feet away was an F-14 Tomcat in full afterburner ready to launch. To my right, about five feet away was a sixty foot drop down to Davy Jones' locker. It was not looking like a good day. I basically had two choices to make: one, become instant toast or two, find out if Davy Jones really does have a locker.

At that moment, I think every flight deck crash training film I had ever seen flashed through my mind and none of them were good thoughts. I had heard of an A-7 Corsair earlier on the Constellation that had done the exact same thing, but when he slammed down onto the flight deck, the nose gear slammed up and pierced the cockpit, right between the pilot's legs. The pilot was OK, but the A-7 was not. No fire, thank God, but it took a while to clear the recovery area. That was the thought I had in my mind.

I jumped up very quickly. The Shooter on cat #2 had seen what was happening and immediately went into an abort mode, shutting down the F-14. The A-7 slammed into the deck, but the nose gear held and did not go through the cockpit. The pilot was a little shaken, as was I, but we both managed to get the A-7 out of the recovery area without having to change skivvies. I was fine after that, but it did shake me up a little bit. Smitty came over and asked if I needed a break; I took him up on his offer. As my dad would say later on when I relayed this particular story, "Builds character, doesn't it?"